💥Windstream Blown Into Bankruptcy💥

Windstream Files for Bankruptcy (Long Litigation-Induced Bankruptcy)

Well, that sure escalated quickly.

Days after being on the wrong-side of a ruling by Judge Jesse Furman in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in U.S. Bank National Association v. Windstream Services, Inc. v. Aurelius Capital Master, Ltd., Case No. 17-cv-7857 (JMF), Arkansas-based Windstream Holdings Inc. ($WIN) — a provider of (i) network communications and technology solutions for businesses and (ii) broadband, entertainment and security solutions to retail consumers and small businesses in small rural areas across 18 states — filed for bankruptcy in the Southern District of New York (along with 204 affiliates). The upshot of Judge Furman’s decision is that, as of the petition date, the debtors are on the hook for approximately $5.6b in funded debt obligations. And they are f*cking pissed about it. Likewise, a number of investors (Blackrock, Vanguard), hedge funds (Elliott Management Corporation, Brigade Capital Management LP, PointState Capital LP, BlueMountain Capital Management LLC), retirees (California Public Employees’ Retirement System) and counterparites (AT&T…yikes…a $49.5mm unsecured claim) are likely also a wee bit miffed this week. But remember: “💥Aurelius is NOT Litigious, Y'all💥” and “The Rise of Net-Debt Short Activism (Short Low Default Rates).” MAN THIS IS SAVAGE.

In the press release announcing the debtors’ bankruptcy filing, CEO Tony Thomas said:

“The Company believes that Aurelius engaged in predatory market manipulation to advance its own financial position through credit default swaps at the expense of many thousands of shareholders, lenders, employees, customers, vendors and business partners. Windstream stands by its decision to defend itself and try to block Aurelius’ tactics in court. The time is well-past for regulators to carefully examine the ramifications of an unregulated credit default swap marketplace.

“Windstream did not arrive in Chapter 11 due to operational failures and currently does not anticipate the need to restructure material operations,” Thomas said. “While it is unfortunate that Aurelius engaged in these tactics to advance its returns at the expense of Windstream, we look forward to working through the financial restructuring process to secure a sustainable capital structure so we can maintain our strong operational performance and continue serving our customers for many years to come.”

Eeesh. Here’s a live shot of Mr. Thomas after getting board authorization for the bankruptcy filing:

In turn, here’s a live shot of Aurelius’ Capital Management LLP’s Mark Brodsky:

(Yes, we thought that Mike Tyson was an apt choice here given how hard this punch landed). Aurelius absolutely loves this sh*t.

For those of you who are new to this sh*tshow, here is a link to Judge Furman’s decision. If you don’t feel like reading 55 pages of boring legalese, here is a summary by Weil Gotshal & Manges LLP. Therein, Weil succinctly recounts (i) the 2015 transaction wherein Windstream created a new holdco to enter into a sale-leaseback transaction with a spunoff real estate investment trust, Uniti Group Inc. ($UNIT), and (ii) the 2017 transaction wherein WIN obtained post facto consent from a majority of noteholders to waive the resultant (alleged) default in exchange for money money money and new notes. To these events, Aurelius was like:

And Judge Furman concurred; he ruled that the 2015 transaction was a prohibited sale-leaseback transaction under WIN’s indenture and invalidated the 2017 consent solicitation, awarding Aurelius $310.5mm plus interest. As justification, the Judge basically concluded that (i) the new holdco was just a legal shell/pretense, (ii) the subsidiaries who previously owned the assets continued to use those assets, (iii) the subsidiaries exercised effective control over the assets, (iv) the subsidiaries were effectively paying rent under the lease by way of dividending payments up through the new shell holdco, and (v) WIN had admitted to nine state regulators that the transferor entities would get the benefit of the leaseback. In other words, for all intents and purposes, the new holdco’s name was on the transaction but no legal abracadabra was going to fool anyone into thinking that the original transferring subsidiaries weren’t the real parties under the lease.

Yet, suffice it to say, this result was not at all what WIN expected. Here was WIN’s statement relating to the decision. And here is Aurelius laughing and pointing at WIN as it responded to WIN’s statement. They wrote:

We take no pleasure in Windstream's resulting financial predicament. Windstream could easily have averted it – first by not playing fast and loose with its noteholders in 2015, hoping nobody would hold the company to account, and second by settling. Instead, Windstream wasted an exorbitant amount – more than would have been needed to settle with us at the time – on an ineffective exchange offer and then on litigation.

In our view, a management and a board with an extreme and unwarranted assessment of Windstream's legal case chose to bet the company. The company lost.

They take no pleasure, huh? We find that a bit hard to believe. Why? This is a live shot of Aurelius writing its response:

Check out the rest:

According to its statement last Friday, Windstream now intends to appeal. This is welcome news for our fund, as it will require Windstream to post a surety bond exceeding $300 million. That surety bond will pay in full the notes our fund owns when Windstream loses the appeal. We are happy to take the surety company's credit over Windstream's.

To noteholders who chose to play the company's game even after it had broken its promise, we wish you luck with your exchange notes. Between their dubious status and their OID risk in bankruptcy, we suspect you will need it.

🔥💥🔥💥

Dubious status? What dubious status? Per Weil:

While the court held that the notes issued under the Indenture—i.e. any notes outstanding prior to the exchange offers—are accelerated, it specifically declined to hold that the New Notes issued in the 2017 exchange are invalid, giving rise to confusion over their status. (See Op. at 51). Because the Court held that the Third Supplemental Indenture containing the waiver of default was invalid, it follows that all holders of the 2023 Notes at the time of the exchange—not just Aurelius—should be entitled to a judgment. At least some of this confusion could have been obviated by a finding that all holders of the New Notes are to be restored to their status quo ante as it existed prior to the exchange offers. While this ruling would also raise complex issues, it would better accord with the operation of the Indenture.

Right. That probably would have made more sense. Insert some litigation here. And Weil doesn’t otherwise comment one way or another as to whether the Judge took liberties by extending his review outside the four corners of the legal document. They simply state:

The Court’s reliance on Windstream’s admissions is a reminder for counsel to consider not just whether a proposed transaction fits within the literal terms of the debt documents, but also whether it is: (1) consistent with the company’s public statements; (2) supported by the contemporaneous factual record; and (3) whether the economic substance of the transaction is consistent with its characterization.

But Professor Stephen Lubben did. He writes:

The court readily concedes that the plain language of the indenture does not cover the transaction on its face. Rather the court repeatedly argues that the “economic realities” of the transaction bring it within the terms of the indenture.

In essence, the court has granted Aurelius covenant protection that it (and its predecessors) were not savvy enough to negotiate in the first place. That’s the kind of interpretive stretch that law professors expect to see with sympathetic plaintiffs – the classic “widowers and orphans.” But Aurelius?

As the author of a law school corporate finance text, I’ve read my share of these sorts of opinions. I often tell my students that the one constant theme running through the bulk of corporate finance jurisprudence is that “if you want protection, you’d better contract for it.”

The Windstream opinion represents a clear departure from that trend. Instead, the theme seems to be, “I know what you really meant.”

Meh. We could get an ID with a picture of Chris Hemsworth next to it but that doesn’t make us Chris Hemsworth. You get what we’re saying?

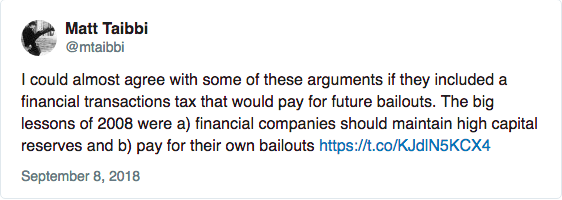

Anyway, Lubben also reiterates a prior alarm that credit default swaps are having a deleterious effect on the market. He writes:

Long ago I warned that the growth the of the CDS (credit default swap) market represented a threat to traditional understandings of how workouts and restructurings are supposed to happen. The recent Windstream decision from the SDNY shows that these basic issues are still around, notwithstanding an intervening financial crisis and resulting regulatory reform.

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine adds:

“…the universal assumption is that Aurelius has also bought a lot of credit-default swaps that will pay out if Windstream defaults on its debt: By pushing Windstream into default, Aurelius will make a profit on its CDS, even if it loses money on the bonds. And, look, in general, I am all for CDS creativity, but here even I find it distasteful. “We, along with others in the market, found Windstream’s arguments that Aurelius pursued this litigation in bad faith and in order to ensure a payout on its CDS to be compelling,” wrote analysts at CreditSights.”

The Financial Times writes:

“The judge just missed . . . the big picture”, said one hedge fund set to lose money from the ruling, noting Aurelius’ position in credit derivatives. “This decision opens a Pandora’s Box and is going to encourage a lot of aggressive behaviour”.

Ugly fights between creditors and companies over clauses in dense legal agreements are nothing new. But Aurelius’s win has companies suddenly wondering what enterprising hedge fund is now combing through their past wheeling-and-dealing, looking for an obscure technical violation that could result in a ransom payment. Debt investors have recently targeted Sprint/T-Mobile and Safeway over similar covenant technicalities.

Matt Levine rightly continues:

“Windstream’s accusation of market manipulation is nonsense,” says Aurelius, and that is completely correct as far as it goes. As far as Windstream is concerned, all that Aurelius did was read its bond documents, assert its rights under those documents, go to court to argue its position, and win in court. None of those things could be market manipulation. If Aurelius also bet in the CDS market that it would be correct, well, (1) that doesn’t sound like manipulation to me and (2) Windstream wasn’t selling CDS so the integrity of the CDS market isn’t its problem.

But of course the overall result is very much Windstream’s problem: Windstream is bankrupt now because Aurelius came after it, and it’s hard to imagine Aurelius coming after it if Aurelius hadn’t bought a lot of CDS on Windstream first. (Windstream’s other bondholders were very willing to forgive Windstream’s covenant violation, tried to help it fend off Aurelius, and are now facing huge losses due to Aurelius’s activism.) It is not hard to sympathize with Windstream’s view that something is wrong with the CDS market, if this is the result.

Sure, but, like, maybe don’t hate the player, hate the game??

Putting aside the CDS aspect, the (one) comment to Mr. Lubben’s piece is indignant and raises valid points. Sisi Clementine (cute name) writes:

WIN opco spun out the assets, and then holdco leased them back. What did holdco do with those assets? Well, they allowed opco to use the assets freely. Hmm, okay, but then how did holdco pay rent? Well, opco pays a dividend to holdco in the exact rent amount and then holdco pays it to the spinoff. I see. So do holdco and opco share the property? No, holdco has no separate address, employees or business, so the property is for the exclusive use of opco. Umm, does this smell funny to anyone else?

In fact, it does! The judge! In his ruling, he cite a body of case law on leases that shows that a person who makes regular fixed payments in exchange for the exclusive use of a space is the holder of a lease, regardless of whether a paper contract exists. Personally, I find this conclusion to be on firmer legal ground than Windstream's version of events, which is essentially that the lease goes to holdco and then disappears inside the company in an opaque cloud of trust.

Of course, the Judge did not rely exclusively on this reasoning for his judgment. He added two further, independent reasons why the opco was party to the lease. The first is that Windstream, as a regulated telecom carrier, required approval from state regulators for the transaction. When regulators expressed concern, WIN formally told them it was a sale-leaseback transaction to reassure them. The judge then estopped WIN from changing its story in court. The second independent reason is that WIN opco signed 120 subleases on the space. You cannot sublease without a lease, therefore opco must have had a lease in order so sign those contracts.

What Prof Lubben has not told you, is that the court's habit of siding with businesses in matters of likely covenant breaches is only about a decade old. Market participants have found it troubling that businesses are given the benefit of the doubt as long as they have some legal explanation, no matter how tenuous. Management has grown increasingly brazen over the last few years, often with the backing of their private equity sponsors. The fact that it has taken an opportunist like Aurelius to right this wrong is proof that there are no heroes here. But maybe one day the legal establishment will wake up and end this plainly predatory behavior. (emphasis added)

Apologies, Clementine, but Aurelius may have achieved the impossible with all of this:

Aurelius, of all funds, may actually live long enough to see itself become the hero. In contrast to Levine, Clementine is saying that WIN is the predator, NOT Aurelius! And Clementine isn’t alone:

Levine adds:

You can choose to view Aurelius not as an interloper messing up a perfectly amicable situation between a company and its bondholders, but rather a vindicator of the rights of bondholders against an overbearing issuer. The story might be that, in 2015, Windstream flagrantly violated the terms of its bonds and dared its bondholders to do something about it, and those bondholders were too meek or confused to defend themselves. They were simple long-only credit investors, they don’t have the time or inclination to sue, their positions weren’t concentrated enough to make it worthwhile, they weren’t expert document-readers, or whatever: They were mugged by Windstream and had no practical way to stand up for themselves. But eventually they (well, some of them) sold their bonds to Aurelius, and Aurelius stood up for bondholders’ rights. And now other bond issuers will think twice before trying to steamroll their bondholders in the future, knowing that Aurelius may be lurking to call them on it.

As for Windstream placing the blame at Aurelius’ feet? Aurelius had something to say about that too. Per Barron’s:

“Windstream’s accusation of market manipulation is nonsense,” says an Aurelius spokesperson. “Rather than whining about us and Judge Furman, Windstream’s management and board should engage in much-needed introspection. They alone caused the company to enter into a terrible sale-leaseback and prejudice its bondholders by breaking its promises to them.”

Things really ARE getting weird in distress these days. Just imagine what will happen when we finally tip into an actual distressed cycle…? Will less boredom lead to less “manufactured” action??

So, where do things stand now? The bankruptcy court held the first day hearing yesterday and generally the debtors got all requested relief approved (including access to $400mm in interim funding — out of a committed $1b — under the DIP credit facility). This will obviously address the immediate liquidity crunch the company faced upon the post-judicial-decision acceleration of its debt.

So now all focus turns to Uniti Group Inc. which, itself, isn’t exactly unscathed by all of this.

Source: Yahoo Finance.

Uniti’s future is clouded because the company gets more than two-thirds of its revenue from its former parent, with a master lease giving Windstream the exclusive right to use the Uniti’s telecommunications network. That lease could be in jeopardy because of its sizable expense to Windstream -- more than $650 million a year -- and bankruptcy proceedings often lead to revision or rejection of existing contracts.

Windstream relies on Uniti to serve its customers, and it’s also Uniti’s biggest customer, making a complete cutoff of their relationship less likely.

So, yeah. There’s that. There are also those — notably, the ad hoc group of second lien noteholders — who may agitate for the debtor to go after Aurelius for its “manufactured default.”

Not for everyone (if it happens…we’re dubious). In fact, we’re pretty sure none of WIN, its debt and equity investors, or its other interested parties find this “interesting” at all.